Fabrics and wallpapers with an expressionist, hand-painted aesthetic have been making serious waves in design. Effect Magazine speak to some of the key producers to find out how they do it and why the world is taking note.

We’re used to hearing about artists creating as they go along, spontaneously. We’re familiar with the free-spirited French Impressionists and their loose brushwork, intended to capture ever-changing light and weather conditions. The Abstract Expressionist movement, which originated in New York in the 1940s, legitimised the use of gestural brushwork for its own sake, particularly on monumental canvases.

By contrast, we don’t normally associate design with self-expression, perhaps because it has a duty to be functional and is often mass-produced. The craft world is different – nearer to fine art since designer-makers develop a personal language and don’t always prioritise functionality.

Yet there’s a strong tendency today for designers – particularly in the textiles and wallpaper worlds – to experiment with techniques that encourage greater spontaneity.

Designers approach this in a number of ways, sometimes straying from traditional printing techniques or improvising by using unconventional tools or translating their own expressive hand-drawn designs on to paper or fabrics. These designers eagerly court chance and spot creative potential in the accidents that inevitably occur during the design process. They relish uneven patterns, painterly splodges and smudges that give a sense of movement and look carefree and joyous.

Some designers take inspiration from ancient crafts such as marbling, which appeals for its unpredictable striations. Japanese crafts such as marbling-technique suminagashi, which means “ink floating”, and shibori, meaning “to wring, squeeze or press” – a tie-dying technique – currently fascinate young designers.

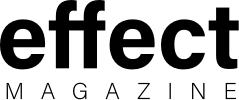

One company in the vanguard of this approach is Timorous Beasties, established in Glasgow in 1990 by Paul Simmons and Alistair McAuley, rebels from the get-go. They caused a stir with their Glasgow Toile of 2004, a mischievous take on the traditional toile de Jouy – the French fabric normally associated with charming pastoral scenes – which in their hands depicted Glasgow’s working-class Firhill area, complete with tower blocks and winos boozing on park benches.

“We’re satirising the incredibly conservative textiles world,” Simmons confided at the time, and their disruptive approach has seen them produce unruly versions of traditionally ordered patterns ever since on wallpapers, fabrics, rugs and cushions.

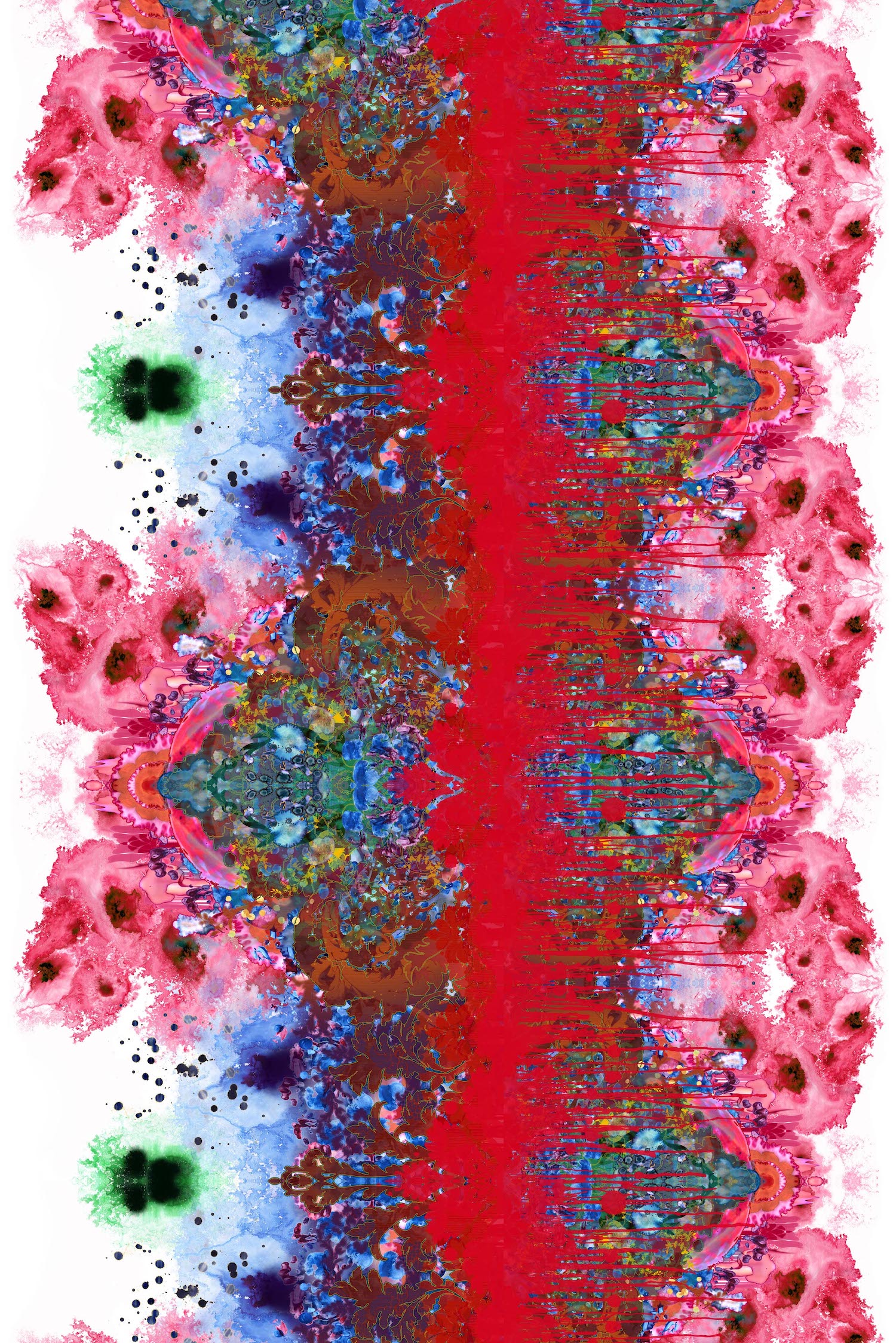

In the late 1990s, the duo created a wallpaper called Euro Damask that challenged the 1,000-year-old convention of the damask pattern, dissolving its clean outlines. Two later related patterns, Thunder Blotch and Omni Splatts, created in the 2010s and still available today, blurred a damask pattern more radically with bleeding, dripping edges and amorphous, splattered blotches of ink.

“From the start, what was different about us is that everything is originally hand-drawn,” says Simmons. “Later on, we began to scan these original drawings, rearranging the scans to create repeat patterns, then digitally printing them. But we want the end result to look spontaneous.” A good example is the design Graffiti Horizon (below) with its multicoloured, spray-painted effect.

The genesis of the company’s best-selling design, Pinyin Tree (below) – a tree whose foliage is informally represented by smudges – was accidental, Simmons says. He was apparently mopping up ink spilt on the printing studio floor and, on the spur of the moment, started making marks on paper with the mop.

In Timorous Beasties’ world, no method is out of bounds, however idiosyncratic. But their freewheeling approach has historical precedents, Simmons points out: “Unconventional techniques have always existed: sponges were used to depict clouds on old Chinese wallpapers.”

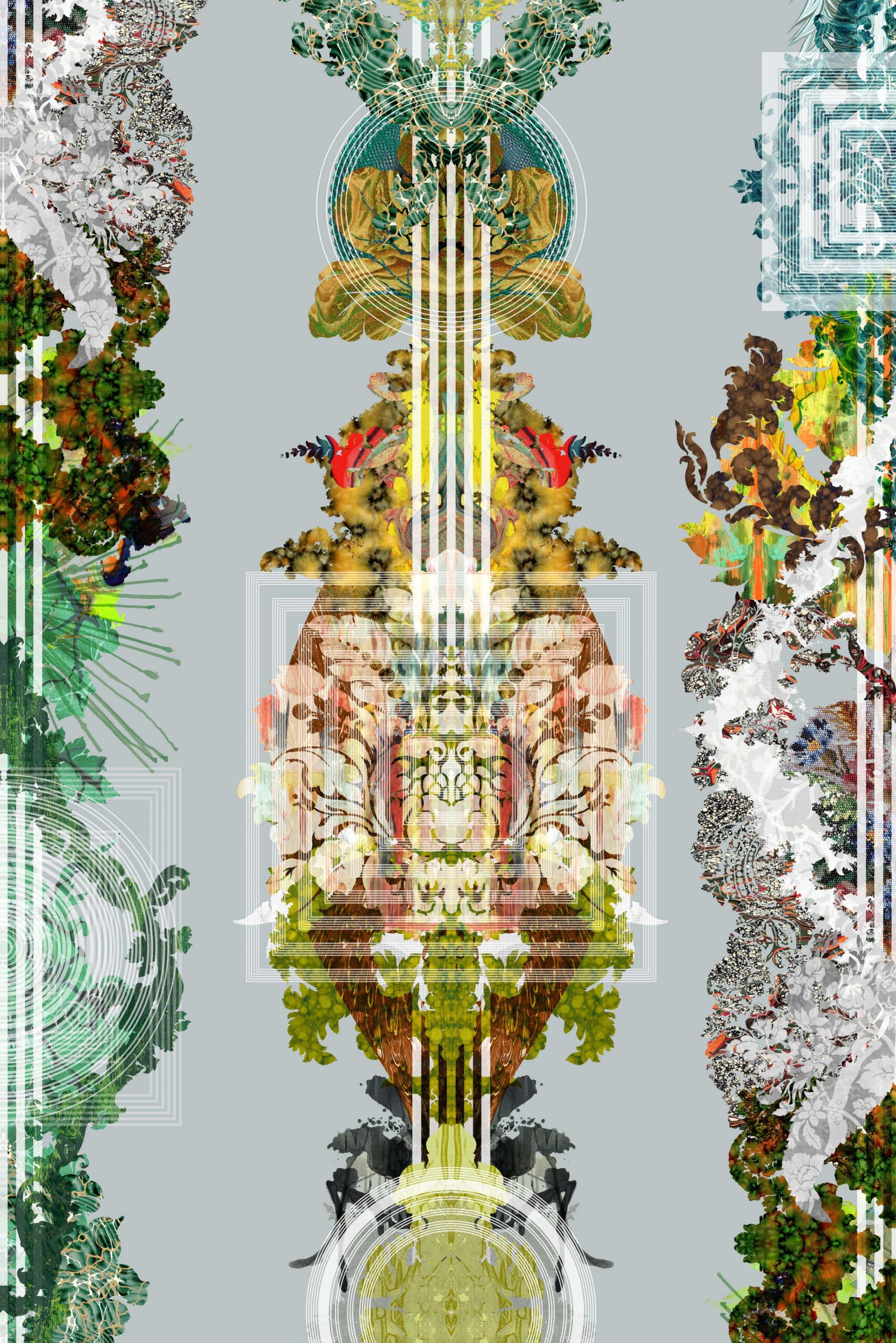

Margate-based printmaker and illustrator Natascha Maksimovic (pictured below), founder of her brand Nat Maks, also plays with chance when creating her wallpaper using the suminagashi technique. To make this, she carefully squirts oil-based inks onto water contained in a large paddling pool. By waving a fan just above the water or blowing on it, she encourages the ink to move in various directions before laying a large sheet of paper on the water. The inks’ swirling striations in the water transfer on to the paper, resulting in strongly decorative, free-form, organic marks.

Although she deploys a craft practised by calligraphers as far back as the 12th century, her marbled papers look modern not classical, thanks to their fresh colours, such as fluorescent orange, turquoise and lemon yellow. “I don’t just want to preserve this craft but push it into a contemporary, surprising context,” she says.

Berlin-based artist Sarah Illenberger also finds beauty in unpredictable marks. Her Unscripted textile panels for Kvadrat are derived from her personal collection of scribbles made by people testing pens and crayons in shops before buying them.

Her diaphanous textiles bear blown-up scribbles that have a naïve, childlike quality. These scribbles appeal to Illenberger for their anonymity and unselfconsciousness, although she also compares them to the work of American artist Cy Twombly, known for his paintings featuring graffiti-like marks and scrawls. “Some interiors are so static and perfectly curated that I wanted to create a gesture that freshens things up,” she says of Unscripted.

Another Kvadrat fabric in the hand-drawn vein is its Murale textile for the brands’ subdivision, Sahco, which features a freely drawn line drawing of a woman. And Italian textiles brand Rubelli’s Derbyshire Spring cotton fabric has a painterly quality, with its impressionistic depiction of birds, berries and foliage.

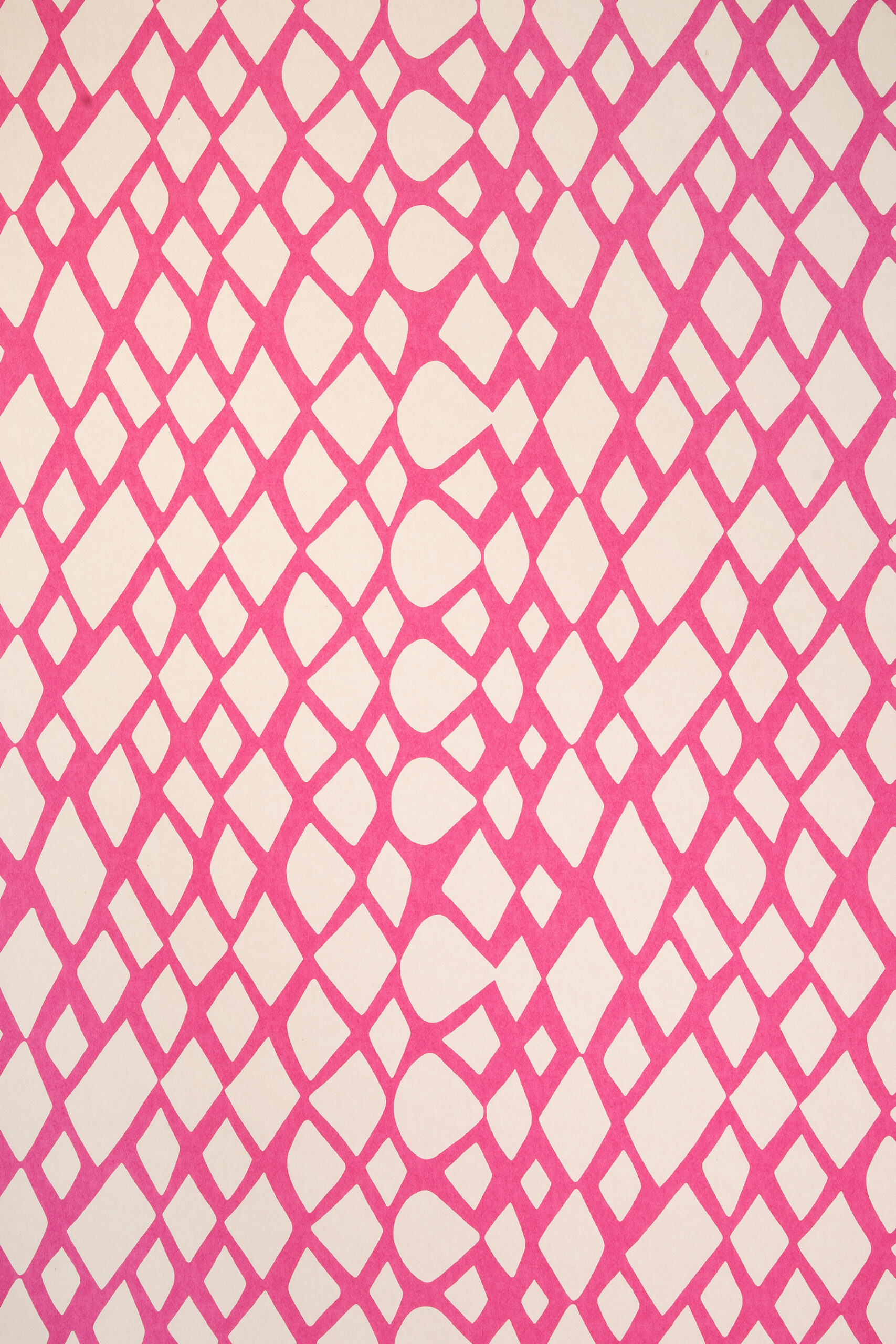

For Swedish artist and illustrator Siri Carlén, who is a fan of shibori, some pastel drawings she did of exaggerated animal prints were the inspiration for her Monster collection of fluffy mohair throws and thick, shaggy rugs for Swedish homeware brand Hem.

“The drawings are a bit messy and behave in ways that are outside my control – and that’s exactly what I like about them,” she says. “There’s a texture to them that almost reminds me of fur, so their transformation into textiles felt perfect.”

All these designs appeal because of their human qualities and hand-drawn aesthetic that can never be accused of slick, soulless perfection. Another good example is Christopher Farr Cloth’s exuberant wallpaper collection inspired by the archive of the late British abstract artist Sandra Blow, whose work was expressive, colourful and informal (she often made collages using torn paper or canvas and cut-outs similar in style to those of Matisse).

These wallpapers convey the boldness of Blow’s work, her original use of colour, and brushstrokes that capture unique moments in time. They have a freshness and vitality that could never be manufactured.

Effect Magazine is brought to you by Effetto