In the service-based city of modern London, a surprising array of artisan workshops and manufacturing industries are still to be found, writes author of Made in London Clare Dowdy

In the eastern borough of Barking and Dagenham, London’s manufacturers are welcome. A four-storey building called Industria has just gone up with space for 47 small-and medium light-industrial enterprises, and an all-important helical ramp for lorries. The work of architects Haworth Tompkins with Ashton Smith Associates, it’s billed as the UK’s first such multi-storey scheme.

This is a sliver of good news for the capital’s makers, because between 2001 and 2020, Greater London lost nearly 4,000 acres of industrial land to other, predominantly residential, uses, according to the Greater London Authority (GLA). In central London alone, about 50 per cent of industrial land has disappeared since 2001, says Peter Murray, co-founder of New London Architecture.

And yet despite the recent direction of travel from industrial to residential, the city has a surprising number of makers. Many of those that have hung on are thriving, and the numbers are growing. Who’d have thought that down alleys, in railway arches and on off-the-beaten-track industrial estates, London is producing everything from umbrellas to propellers and terrazzo to textiles.

This local energy was on show at south London’s Staffordshire Street gallery during the London Design Festival. The show 11:11 featured work by Grain & Knot, whose studio is in New Cross, Jan Hendzel Studio in Woolwich, and Sedilia, who make their upholstered furniture between Brixton and Clapham.

“Furniture-making had seemed doomed,” remarks Mark Brearley in his forward for Made in London – From Workshops to Factories, but now there are 230 bespoke and small-batch makers, like those who exhibited as part of 11:11, and Gavin Coyle Studio in Walthamstow.

Made in London champions furniture makers like Coyle, and a host of other businesses. As the writer of these 50 profiles, I got to ask the owners why they’ve made London their home. After all, there are bigger, cheaper premises elsewhere.

For some, like Tate & Lyle Sugars, it’s historic. The firm was set up on their existing 50-acre site in Silvertown in 1876, and it would be too costly to move. They’re one of the few lucky ones, along with tin can maker William Say & Co and Ormiston Wire, which own their sites.

For others, like Borough silversmith Grant Macdonald London, it’s about the talent pool. As well as their own highly-skilled staff, “there is a network of artisans nearby to call on for skills like cutting, enamelling and embossing,” founder George Macdonald says in Made in London.

The company exports 90% of its products – trophies, clocks, ceremonial swords and the like – to clients including Middle Eastern royalty. Their London postcode – the capital has a long history of producing quality gold and silver items – is also good for business.

In fact, plenty of makers suck up the cost and hassle of being in the capital by literally capitalising on their address. As well as Grant Macdonald London, others making the most of the ‘Made in London’ badge include Cox London, producing lighting and furniture in Tottenham; and London Stone Carving, which was set up in 2015 by four art school friends in Peckham. William Say, meanwhile, stamps ‘Made in London’ on the base of some of their tins.

But the capital isn’t just about image – it’s the logistics too. Global restructuring of the world’s supply chain has been caused by multiple economic changes: the coronavirus pandemic, Brexit and the war in Ukraine. The 2022 report by the manufacturers’ association Make UK and Infor, Operating Without Borders — Building Global Resilient Supply Chains, claims that in the past two years, three-quarters of companies have increased the number of their British suppliers.

Or as John Leveridge, co-owner of Aimer Products, puts it in Made in London: “Customers want to buy British because of the nightmare of getting stuff from Europe.” For years, Enfield-based Aimer mostly made petrochemical glassware, but it now has a new consumer business with lighting designer Andrew Print Leverint producing glass lighting.

Similarly, William Say – whose 50 shop floor staff make 8m items a year – is a beneficiary of reshoring. Supply chain issues in the far east “have accelerated the general trend for buying local. There’s a growing thirst for knowledge about how stuff is made, and it adds some value for customers,” says the firm’s director, Stu Wilkinson.

Being in London also makes sense if you’re making for your immediate market – the capital’s population is rising and in 2021 passed 9m for the first time. This is good news for the chocolate makers like Prestat, and the mushrooming artisan bakers and craft breweries.

And the evolution of West End musicals into ever more fantastical extravaganzas means staff at Marcus Hall Props are able to send the props they make in Lewisham to the stages of Mary Poppins, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Frozen, and bring them back for repairs in time for the evening show.

Likewise, the two biggest places of making in central London are the National Theatre and the Royal Opera House, where specialist seamstresses, hat makers, propmakers and the like are on site.

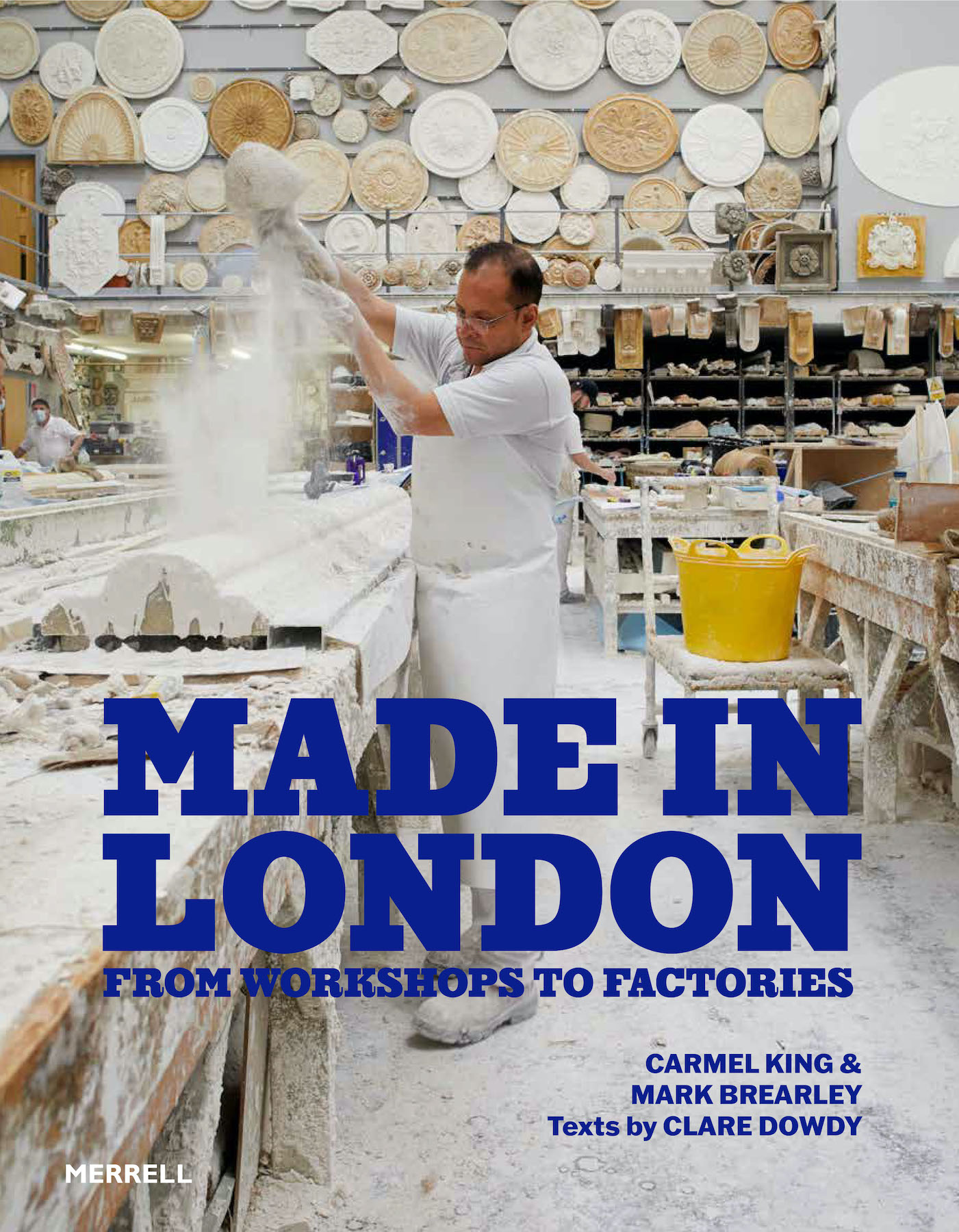

The arches, columns, ceiling centrepieces, roses and cornices made by decorative plasterwork firm George Jackson in Sutton adorn Buckingham Palace, The Ritz, Café Royal on Regent Street and Chelsea Barracks. Barber Wilsons & Co’s taps have been transported from its original 1905 building – complete with Crittall windows – in Wood Green to The Connaught, The Grosvenor and the Royal Household.

Kashket & Partners have to be 30 miles from Wellington Barracks, because they make military dress uniforms in their Tottenham workshop for beefeaters, colonels and royalty. And Electro Signs’ neon signs (pictured at article head) in Walthamstow have lit up Raymond Revuebar in Soho and the film sets of Superman IV.

It makes sense for specialists to be able to invite customers to visit – hence Grant MacDonald’s light, airy new building in Southwark. Similarly, textile and wallpaper printing firm Ivo Prints was sought after by fashion’s elite including Ossie Clark, Celia Birtwell, Zandra Rhodes and Vivienne Westwood when it set up in the 1960s. Now, a major customer is interiors brand Christopher Farr.

While some long-standing businesses were founded by Brits – William Say, Tate and Lyle, umbrella maker James Ince, Brompton foldable bicycles, Aimer Products, sixth-generation wire rope manufacturer Ormiston Wire – others were started by plucky new-comers. Czech immigrants Ellen Haas and Ivo Tonder were behind Ivo Prints. Russian milliner Alfred Kashket made felt hats for Tsar Nicholas II before coming to the UK to set up Kashket. And in the late 1800s, Sigmund Diespeker from Germany and Giovanni Mariutto from Italy set up Bermondsey’s terrazzo and natural stone firm Diespeker & Co. There’s an argument, made by Brearley among others, that a good city needs a good mix of activities, workplaces and people. Manufacturing should be a good fit, and maybe if more Industrias are built, more makers will be inspired to call London home.

Read more: Design | Furniture | Interiors | Makers | Dealers | London | Interior Designers