Effect Magazine talks to architects, anthropologists, designers and the author of Sauna – The Power of Deep Heat about the design evolution of saunas from caves to luxury hotel spas, and their ongoing cultural significance

What started out as a super-practical, multi-functional space thousands of years ago, has evolved into a life-style status symbol for ultra-high-net-worth individuals. And yet the fundamentals of a good sauna experience have changed little since sweat bathing became a thing 10,000 years ago. If a Stone Age designer had been given a brief back then, it would have been for an enclosed space that heats up easily, and where steam can be created.

Sauna’s first manifestation was as a cave, and then as a pit dug into the ground, explains Dalva Lamminmäki, folklorist and doctoral researcher of sauna culture at the University of Eastern Finland. Stones were piled up on the floor of the pit and were heated by a campfire. “Once the stones were hot, the pit was covered with wattle, thatch or peat, and water was thrown on the stones to create steam,” she says.

By the middle of the Iron Age (700–1BCE), bespoke sauna buildings were becoming a thing. Borrowing from earlier manifestations, windows were eschewed to keep the heat in. Emma O’Kelly notes in her book, Sauna – The Power of Deep Heat, that in Ireland and Scotland, “stone huts with tiny entrances and no windows have been used, on and off, since the Bronze Age (2300–700BCE)”. They were typically built into hillsides and near open water or a well.

While the sauna room as we know it today has Finnish roots (‘sauna’ is a Finnish word), this type of sweat bathing has been found all over the world, “from the Ottoman hammam and Mayan temazcal to the Japanese mushi-buro and kama-buro… and the banyas of Russia”, O’Kelly explains.

There’s a practical reason for this, according to Jake Newport, co-founder of UK-based sauna design and manufacturer, Finnmark. “Sweat bathing is a very efficient way of cleaning everyone in a large family. It would have been far easier to make a room very hot than to boil up water for everyone. After being in a hot room, it’s a relief to get into cold water to wash. It’s time-efficient and cost-efficient.”

From the time of pit saunas until the industrial age, saunas were the venue for many chores. As well as washing, they were used for cooking, drying flax, making soap, doing the laundry, tending to the sick, preparing the dead for burial and giving birth, says Lamminmäki. “The sauna was also used as a sleeping place and place to meet someone in secret,” she adds.

In fact, so important was the bathhouse of our forefathers, that “it was often the first building erected on a homestead where a family would sleep, eat, cook and wash,” O’Kelly writes in Sauna. “The dark, womb-like space was essential to life in the cold, damp climates of northern Europe.”

Public saunas lost their appeal in the early 20th century – in urban areas, at least – as bathrooms became standard. “Those who had the means were installing bathtubs in their homes and no longer needed to wash in communal baths,” O’Kelly writes. “Meanwhile, in less-developed rural areas, there was a national drive to create more community saunas. Between 1920 and 1950, 10,000 public saunas were built in Sweden.”

The first thing a Finnish architect will discuss is where to put the sauna and how will it look.

Jake Newport, co-founder of Finnmark

Technological progress led to the invention in Finland of electric saunas. The result was saunas being installed in spas, gyms and hotels around the world.

As private saunas have proliferated in Finland (3.3m in total for a population of 5.5m), it’s become the key element for any architect. “The first thing a Finnish architect will discuss is where to put the sauna and how will it look,” says Newport.

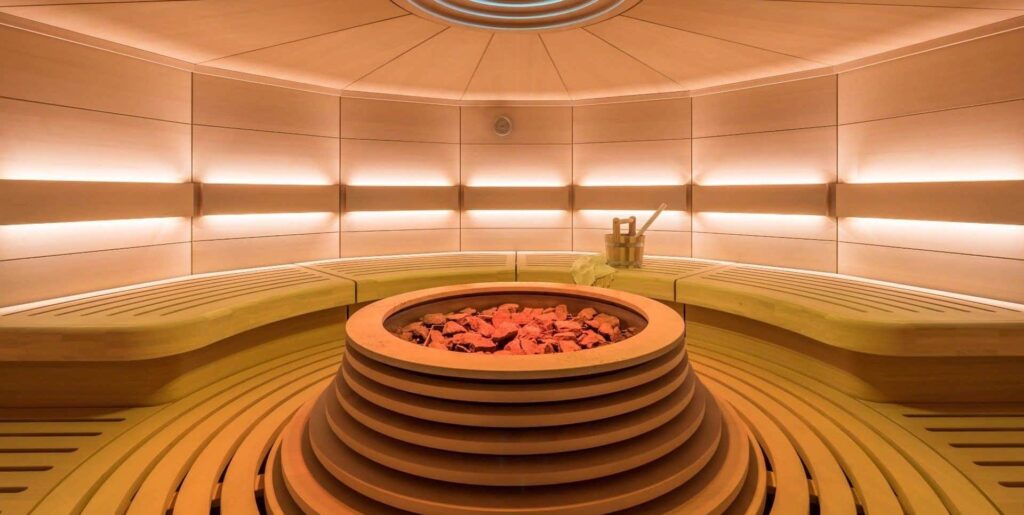

For modern-day saunas, Newport defines the basic requirements: correct fresh air ventilation – to avoid getting a hot head and cold feet – the correct type and thickness of insulation, thorough vapour sealing to prevent damp and interstitial condensation, a heater with a large stone capacity (the more stones the better, and the softer the steam), and of course, the use of water poured over the sauna stones to create steam.

Then there’s the all-important benches – they’ve got to be the right height. The Finns say the best ceiling height is two clenched fists above the head of the tallest sitter.

Timber is also a factor. In the early days, abundant and cheap spruce and pine were common, followed by aspen and alder. More recently, some timber is getting the thermo treatment, making them more durable. And there’s now even a sauna ply.

Helsinki’s new public sauna Löyly (meaning ‘steam’ in Finnish) is designed by architecture firm Avanto and fashioned from more than 4,000 planks of precisely cut heat-treated pine. Avanto also produce a home sauna, AITO, constructed from spruce-based cross-laminated timber.

Timber works well for benches and cladding, but not for floors, because it attracts moisture and dirt. Better options are anti-slip porcelain or stone tiles, or even polished concrete. Newport has noticed that soapstone is becoming increasingly popular, because it’s “naturally anti-slip, non-porous, non-permeable, and feels very nice to walk on”.

London-based interiors firm Goddard Littlefair has created a string of spas for hotels and homes, from a Four Seasons Hotel in Istanbul to Chelsea Barracks. For the recently-launched Guerlain Spa at Raffles London at The OWO – which occupies a Grade II* Edwardian Baroque building in Whitehall – Goddard Littlefair’s director Tom Blackshaw specified natural stone alongside “a curated palette of neutral tones, enriched with opulent metallic accents”.

One major change is windows. In the old days, windows were either non-existent or small, to help keep the heat in. Now, private clients and even some public saunas have swathes of glazing. “People want big vista apertures,” says Newport, “Our male clients want big windows, while their female partners want tinted or mirrored glass.” Similarly, Avanto’s Aito model can be glass-fronted. However, more glass means extra effort for your heater.

While exclusive sauna experiences – either at home or in fancy hotels and private spas – have a willing clientele among the wealthy, there is a growing appetite for communal saunas, as evidenced by Löyly’s 200,000 annual visitors. And even the private, commercial saunas are now making space for more interaction, in recognition of the wellbeing benefits of being together.

Champalimaud Design in New York has designed spas for Raffles Hotel Singapore, the Gainsborough Hotel in the UK, Beverly Hills Hotel and Hotel Bel-Air in the US. Kajsa Krause, principal and director of strategy, has noticed a rise in “the urge for sharing communal mindful and active restorative experiences. A social concept of wellness has developed rapidly.” This has an impact on designers, who are now tasked by hotel and spa operators to “create spaces that enhance health and social life simultaneously, yet still balanced with various levels of privacy and solitude”. Quite a juggling act for the designer, and if it becomes too stressful they should seek out a relaxing sauna.

Sauna – The Power of Deep Heat by Emma O’Kelly is published by Welbeck Balance

Read more: Design | Architecture | Spas | Wellness | Hotels | Insights